Yakima River, WA

Part 1: Downstream To Ellensburg

By Terry W. Sheely

The Yakima River flows through countless fly fishing journals as a rainbow-rich anomaly in a state desperate for dream streams. Quick and cantankerous in the splintered log jams, widow-makers and shifting rocks of the mountainous upper reaches, and powerful, sullen and grumbling through the sun baked grasshopper grass and broken basalt in the desert canyon down below,the Yakima drifts downhill

for 215 miles like a wet chameleon with a sense of humor that changes disguises every few miles, and chuckles at the consternations of baffled fishermen scattered along the rocks and willows from Snoqualmie Pass to a confluence with the Columbia River near Tri-Cities.

The lowest 130 miles are on a sullen drift through irrigated melons and peppers, wine grapes and attendant pollutants of the lower Yakima Valley; smallmouth and channel catfish water and health department warnings abut toxic fillets.

I struggle to accept that upstream this abused gray river coursing through fertilized farms and belching from irrigation pipes in Wapato, Zillah, and Prosser morphs into the finest trout stream in Washington.

But it does, to the delight of fly fishermen throughout the state and beyond.

The transformation takes place a little north of Selah where the imposing concrete wall of Roza Dam divides the river like a cleaver, segregating the upstream mountain water for trout and caddis flies, leaving the downstream to catfish and pepper fields.

Those upper 85 miles represent the finest flowing dry and wet fly trout water in the

state.

Blue-ribbon is how some describe the rainbow river that glides downhill in the dam-to-dam serpentines between Keechelus Lake and Roza Dam. These 85 miles are storied with wild rainbows, catch-and-release brags, and hatch matching adventures.

In order to present the Yakima River in comprehensive detail it is being presented in two parts. This installment centers on the far upper river, Easton to Ellensburg. Part 2 will cover “The Canyon,” the magical 18 miles of sun-baked bank banging and hopper water between Ellensburg and Roza Dam.

Some hardliners packing three-piece travel rods and attitude sometimes argue the worthiness of this southeast flowing Cascade stream to be measured against Rocky Mountain destination rivers.

Others may lobby for the Methow or upper Columbia. But who listens. In this region the Yak perseveres as Washington’s paradigm of blue ribbon trout hope. And most of us who dip an oar in its cold water, drop Skwalas on the breaklines, or tighten into the electric jolt of a bank feeder find the Yak worthy; very, very worthy.

Steve Worley, routinely puts five guide boats on the river from his Worley-Bugger Fly Co. in Ellensburg. He defines the Yak as “Central Washington's premier wild trout fishery,” and in his eyes the fishing has been improving steadily since the early 1980's when the first set of progressive fishing restrictions was put in place.

Today’s blue ribbon trout fishery was jump started--somewhat reluctantly--in the 1990s when Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, (WDFW) with incessant prodding by fly fishing organizations, agreed to restrict the 75 mile section between the dams at Roza and Lake Easton to a no kill, no barbs, no bait, catch and release trout fishery. Support for trout protection from the salmon-steelhead focused WDFW was at best half hearted. They agreed to the restrictions with a “what-can-it-hurt” shrug and the justification that banning bait, debarbing hooks and putting a stop to catch-and-eat fishing might spare some of its prized but environmentally threatened salmon and steelhead smolts. The original bait ban and trout release restriction has since been extended the remaining miles to the Yakima’s less than pristine source--an outfall culvert from Keecheleus Lake.

Seriously managing rivers for trout fishing is still so far down on the WDFW priority list that it is invisible. Consider that the only somewhat current Yakima trout data now on file at WDFW was developed as addend to spring chinook restoration studies. Repeated requests for trout study money by concerned WDFW field staff have been rejected inOlympia denying state trout biologists basic and critical management data: fish per mile populations, trout growth, fishing pressure, creel census. Insiders confirm that when fish management isn’t steelhead and salmon focused, top WDFW managers still aren’t interested.

The slight is overlooked by most trout fishermen who prefer to embrace the default that resulted in rigid protections that now enhance naturally spawning wild rainbow trout-a first for Washington.

In his breakthrough book, Yakima River Journal (Amato Publishing, 1994), Northwest

Fly Fishing Editor-In-Chief Steve Probasco describes how in 1983 Tim Irish an Ellensburg native, became the first registered trout guide on the Yakima which also made him the first trout guide in Washington, and a bulls-eye for snide snickerings. From the clerks in the state guide licensing office to fellow fly-fishers there was open scoffing at Irish’s idea of trying to guide trout fishermen in a land of steelhead, salmon, sturgeon and even bass.

Today five guide shops specifically work the Yakima, dozens of guided float trips on any given day year-round, and still no WDFW plan for trout management. Not surprisingly, the river appears to be thriving on state neglect.

Steve Joyce cut his guiding teeth in Montana and now works at Red’s Fly Shop, the largest fly and guide operator on the river, running up to a dozen guide boats during seasonal peaks. “I can honestly say the Yakima is a challenging fishery,” Joyce grins. “It certainly has its days where it gives you a glimpse of how good it can be - with fish, and I mean nice fish, feeding on caddis or blue winged olives (BWOs) as far up and down the river as you can see. But it also has its tougher days, where you're forced to think outside the box and work hard to find a player.”

Neither Worley nor Joyce blink when describing the Yak above Roza Dam as premier trout water, and Jim Cummins, WDFW Yakima regional fish biologist agrees, adding that it can also be one of the most intensely fished trout rivers in the state. The effect of that “intense” fishing pressure is unknown, though. Not since 2003 has WDFW put together creel census surveys, angler pressure estimates or trout population censuses to guide future trout management.

Despite rumors of monster browns, 95 percent of the Yakima River trout are rainbow, with a few cutthroat, even fewer brookies and if a brown is around it’s a lonely stray. Most of the brookies are in the extreme upper reaches well above Cle Elum.

Which is where the Yakima is born half-grown, gushing from an outlet culvert in the dam at Lake Keechelus a sour, fish-poor agricultural irrigation reservoir at roughly 3000 feet elevation below the crest of the Cascades adjacent to I-90 east of Snoqualmie Pass. From the culvert it blows downstream past the USFS Crystal Springs campground in a torrent, and while small rainbows, cutthroats, and brookies are sometimes picked out of the eddies, pools and beaver ponds the premier trout water doesn’t begin for another 10 miles until the Yak escapes from Lake Easton the second and last impoundment above Ellensburg.

The catch-and-release rule applies to rainbows, cutts and browns, but not for brookies. In their campaign to ravage brook trout populations in streams with native char, WDFW has made an exception to the no-trout rule, and allows anglers free reign on the non-native brookies between Easton and Keechelus lakes: no daily or size limit on brook trout.

Downstream from Lake Easton the first decent public launch and wading access is at a WDFW site on East Nelson Siding off I-90. Several hazardous miles below is the Bullfrog/Three Bridges access. Both put-ins lead to log jams, widow makers and bottom banging treachery and are not recommended for drift boats or novice boatmen. Adding to the discouragement is that trout in this upper water, above South Cle Elum, are uncommonly small averaging less than 9 inches, compared to 10 inches and up a few miles further downstream. Fishing pressure in this unfriendly water, though, is also down.

The Yak grows its first serious trout legs at and below the confluence of the Cle Elum River (which quick steps under I-90 not far from the confluence) and steadily improves as it swirls and rolls into South Cle Elum (a WDFW launch south of I-90). Called The Flats or Flatlands by local trouters, the Cle Elum stretch is a reasonably manageable chunk of boating water with skitches of public bank access. Here, boat and bank anglers work through a series of braids and runs and green-bottomed pools with two miles of wade and cast access from the Hansen Pond Road.

This winding rock and riffle torrent upriver from Thorp is the sweet love of Ellensburg outfitter Steve Worley. “Above Ellensburg the Yakima offers more diversity, cleanlier water conditions and no crowds.” he says. The little main-street town of Cle Elum is squarely in the center of this water. A couple of miles southeast is a WDFW access/launch at the Teanaway River junction. (From I-90, Exit 85 and follow Old Hwy. 10 toward Blewett Pass Highway 970). This small dot on the state highway map is a major demarcation line for fly fishermen.

Above Teanaway launch are the Cle Elum Flatlands, and below the beginning of Canyon Water. With a few obvious exceptions most of the water downstream from the Teanaway River appears as a blue line in the bottom of a steep-walled canyon well down from Old Hwy. 10, a climb that discourages most bank fishermen. On several occasions though I found it more than worthwhile to slog and skitter the steep grade to fish water well off the beaten path. One excursion did cost me the tip section of a favorite 4 wt. Sage, but it was my fault and I’ve since recovered.

The John Wayne Trail is public path important to bank fishermen. It follows an old railroad grade along the river south and east from Cle Elum. The trail is a popular walk and wade route for fly guys. Mountain bikers sometimes pack in for overnight bike-and-fish. If you go, I recommend packing fly-weights and boots and hiking to fish water in shorts. Any hike in this piece of the world is hot and steep.

Below the Teanaway is where, in my estimation, the Yakima enters Premierdom, spilling into a trouting wonderland for boaters that can be savored for roughly 10 miles; two-thirds of the 16-mile float to a diversion dam take-out at Thorp. (If unchained, a DOT storage site on Hayward Roadbelow Thorp Bridge offers a rough take-out alternative to continuing downstream to the WDFW take-out above the Diversion Dam, and eliminates the Thorp section of river which according to WDFW has the thinnest trout count per mile in the river. There are, however, some large trout--20 inch plus--taken here. Just not a lot of them.

High above the river pinned onto the stark canyon wall is Old Hwy 10 which follows the Yakima at a comfortably lofty distance southeast from the Teanaway access to Hwy. 97 just outside of Ellensburg. At the bottom of the canyon, well below the highway and away from major roads and barking dogs, the river twists and turns, grinds and grumbles through riffles in a slow, steady drop between banks of cottonwood and quakies. Elk, mule deer and coyotes slip into the shadows, and the river offers up every type of river and fishing condition imaginable, pockets for the picking, overhangs, bottomless pools, deep sullen runs, and sweeping tailouts.

A novice at the oars will bang, hang, spin and ricochet but overall there is little truly dangerous water, especially in the fall when October caddis and BWOs are coming off, trees drip with gold, the irrigators have sluiced off all they want and the river runs low and clear.

Bigger trout may hang under cutbanks in the canyon down river from Ellensburg, but the combination of scenery, color and cold, fat 10 to 20 inch rainbows (I’ve heard of 22 inchers here, but have yet to see one) that meshes in the upper Canyon is without parallel. There was a five year stretch when on the last weekend in September I never missed dropping the old Eastside drift boat into Teanaway launch and spinning down river. I need to do that again.

According to those 2003 WDFW studies the Thorp section has the fewest number of rainbows in the river, averaging 244 per mile compared to the river-wide average of 677. The highest concentration per mile is in the lower Canyon section above Roza with1129 rainbows per mile-one trout in every 4 ½feet of river.

It’s easy to see why Worley’s bias favors the upper canyon around Cle Elum.

“The river just gets better from year to year,” he says, adding, “There’s not a significant increase in trout numbers, but yet (we’re catching more) bigger resident trout.

“Hatches are seasonal and change from year to year depending on water flows and conditions. But yes we are seeing thicker denser hatches on average each season. There as an incredible Light Cahill hatch this past September.It was extraordinary.”

Both Worley and Joyce agree that if they had to pick one Yakima River rod it would be a 9’ 5-weight.

Joyce, who fishes mostly below Ellensburg said his rods “would be stiffer than softer, to throw big dries and small dries, and double nymph rigs and still handle heavy stoneflies and streamers. We use a 9' 5X tippet to fish a small dry fly hatch, but typically run 3X to our big dries which helps turn those bugs over to tuck them underneath the brush canopy and rip your fly off of grass stems. For nymphs we run 3X fluorocarbon to the top fly and 5X between flies, and for streamers we run as big as 1X and 2X - again it helps turn the fly over.”

In his 13-years on the river, Worley has settled on, “a floating line for dry fly fishing and nymphing. Streamers are also effective,” he said, recommending, “Tippets of 4x-5x for dry line fishing with surface and subsurface bugs. A short fast sinking tip is also recommended especially during the summer months when irrigation release flows are high and for streamer fishing. Type V or VI in seven foot lengths. Nothing over 10 feet. Too much belly,” he explains.

I asked Worley if forced to settle on one fly and one rod-line combination for the upper river what that outfit would be. His response was unhesitating, “No. 8 Yak Stonefly, using a Scott GII with a Scientific Angler Expert Distance line.”

Packing fly boxes for a trip to the Yak is a bit like picking girl friends and fishing buddies—take your best guess and sort out the fine points as you go.

Depending on where you are on the river, what the weather is doing, water and air temperatures, month on the calendar, water level and clarity and what rock you’re standing on—your pattern selection could run from dainty size 24 midges to lumbering Size 6 Stimulators or fish-size sculpin-imitating dredgers.

Since salmon populations have been enhanced in the trout water the rainbows have been showing a distinctive preference, at times, for flesh flies, eggs, salmon fry and smolt patterns, according to Steve Worley.

When I picked the brain of Steve Joyce it was his opinion that, “Talking about hatches is relative to whether the fish are actually keying in on them - and not necessarily the number of bugs you see.

“For example - we've had some great Skwala years, and some where it seems like the hatch just never really gets going. We've noticed a couple of reasons for this. One is that if we get a big punch of runoff at the beginning or middle of this hatch, it tends to slow it down - if this happens repeatedly, it hasn't fully recovered by the time the Skwala window is past.

"Another reason for slow Skwala fishing can be low water conditions. Even though the bugs are hatching and the river is in great shape, there may not be enough water for those weak side banks to fill up and fish to move into the shallow insides to eat the Skwalas. As a result, fish are fighting for prime lanes on the strong side and all fisherman are targeting the same zones. It doesn’t take them long to learn not to eat there.

“Factors that may tale the edge off Skwala fishing are sometimes conducive to alternative hatches such as March Browns, PMD's, and even BWO's - which are gravel bottom riffle bugs.

“These hatches are productive when water conditions are low enough to define the ledges and seams in the center of the river yet high enough for fish to spread through out the flat water zones.”

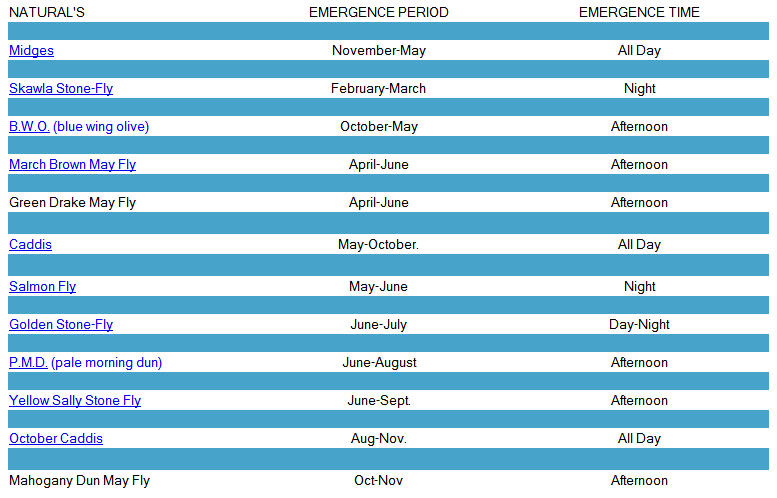

The list of fishable hatches on the Yak is almost baffling.

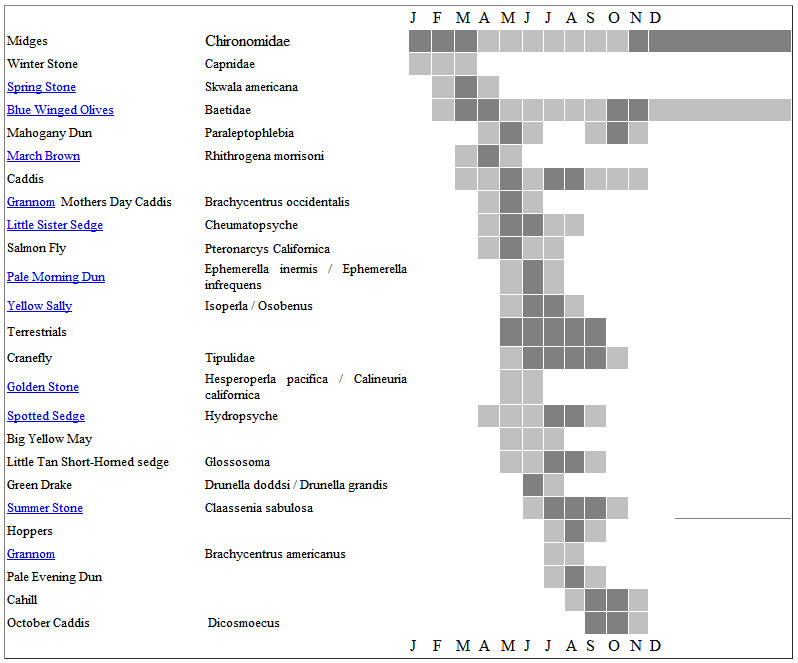

According to charts that Steven Worley posts on the Worley Bugger web site, a well-rounded box needs: BWO, mahogany duns, March browns, caddis (most prolific fly on the upper and lower river), Grannom (Mother’s Day caddis), sedge, assorted salmon flies, PMD, yellow Sally, a wide selection of terrestrials, craneflies, golden stone, spotted sedges, big yellow mayflies, little tan sedge, green drake, summer stone, hoppers, Cahills and October caddis.

And that doesn’t include the basic sculpin imitations. Sculpins are a major food source in the Yak, according to Worley, especially for the largest trout.

While wet and dry variations of midges (Chironomidae), Blue Winged Olive mayflies (Baetidae) and to a lesser degree caddis are the January-December bread and butter patterns nothing blows lightening through the fly shops like stonefly news.

Winter stones (Capnidae) pop out in January, February and taper into March. March is Spring Stone and Skwala time. Summer stones (Claassenia sabulosa )start coming off in June and peak in July, August and September. A hatch of Golden stones (Hesperoperla pacifica / Calineuria californica) comes off in May and June, but it’s usually minor compared to the salmon, caddis and mayfly (Mahogany duns, and green drakes, according to Worley) that also hatch then.

For some Yakima purists heaven is defined in the too-brief flutter of Salmonflies (Pteronarcys Californica) in April, May and maybe June.

Downstream there are grasshoppers, up here caddis and stones. A Yellow Sally Stimulator or heavily dressed caddis will be sucked down by trout feeding on all three. If, for the Thorp to Cle Elum swing, I had to rig with one dry and one wet and nothing else, the dry would be a No. 8 Stimulator and the wet a No. 10 black Woolly Bugger, but if the fish master cuts me a little latitude I’ll cheat in a handful of elk hair caddis and maybe a beadhead Brassie and for sure a Prince.

Best time to fish the Yak?

Spring, according to the guys are on the river every month of the year.

For Worley, “April has to be one of my favorites. The March Brown hatch is fantastic. But September is a pretty fine month as well.

Joyce’s favorite slice of river time flows from March 1 to May 15. “We get so many good hatches during that window that there will be periods during the day where you'll throw both dries and nymphs with success, and the nymphing is usually good outside of that (dry) window. We start with Skwalas and BWO's, then get into the March browns, followed by caddis and PMD's. The pre spawn rainbows are aggressive, feisty, and beautiful.”

There’s always a down side to even blue-ribbon rivers and for the Yakima that downside is valley floor irrigation.

The big reservoirs on the east side of Snoqualmie Pass are Bureau Of Reclamation (BOR) water stores for downstream irrigators in the Kittitas and Yakima valleys, and for several mid-summer months at the peak of the growing season this picturesque river descends into sluiceway hell and the blue-ribbon runs brown. Joyce said he’s seen the river romp from 700 cfs with exposed gravel bars to 9000 cfs with an unbroken surface bank to bank.

Releases into the river are based on irrigation demands and water rights, with no thought to fish or fishers, except for chinook salmon. Typically, the irrigation sluice kicks in late June, peaks in August and drops through September; a timing schedule that benefits orchards, field crops and wild chinook salmon spawn.

According to long-time river fishers cfs flows from 500 to 1500 are ideal for boaters and waders. Wading is a risky option to about 2000 cfs and stronger than that the river is strictly a boat show. Brown water or blue, trout feed and the river is usually clearer upstream from the Teanaway during peak sluice season.

Don’t let the color stop you—it’s always blue ribbon time on the Yakima.

Yakima River Notebook:

When: Open year-round, best March-May before irrigation releases and in late September-October after irrigation ends.

Regulations: Catch and release all rainbow, cutthroat and brown trout, no bait or scents, single barbless hook. Brook trout may be killed in the extreme upper river between Lakes Keechelus and Easton.

Where: Cle Elum River confluence to Thorp, with special attention to the Cle Elum Flats and canyon water below the Teanaway junction.

Headquarters: Either Cle Elum or Ellensburg. Lots of motels and private camping in both towns.

Appropriate gear: 9’, 5-wt. rod, floating and sink tip lines, 5X tippet for small flies, 3X to flip big dries and 1X to 2X for streamers. Waders and good shoes a must, pontoon boats are perfect for this section. Flatlands to Thorp okay for rafts and drift boats. Bring good Polorized glasses, extra tippets and lots of flies.

Useful fly patterns: Caddis and blue winged olives are the most prolific. Also carry plenty of stonefly variations, Skwalas, Stimulators, midges, PMDs, salmon fry, egg and egg patterns. Prince and Woolly Buggers are always welcome. (See chart).

Advisable necessities: Breathable waders (Neoprene’s in the winter), polarized sunglasses, plenty of drinking water, day pack, fluorocarbon spools for tippets, sun protection, big hat.

Non-resident license: Annual freshwater, $43.80, 1-day $14.

Fly Shops and Guides: These local shops offer flies, tackle, current information, fly guides, float trips, and shuttle service for the upper Yakima.

Worley Bugger, Ellensburg,

888-950-FISH,

www.worleybuggerflyco.com;

Red's Flyshop,

Ellensburg Canyon,

(509) 929-1802

www.redsflyshop.com;

Yakima River Fly Shop,

Cle Elum,

509-674-2144

www.tightlinesangling.com.

The Evening Hatch,

Ellensburg,

1-866-482-4480,

www.theeveninghatch.com

Yakima River Angler Guide Service,

Selah

509-697-6327,

www.yakimariverangler.com

Books & Maps:

Yakima River Journal,

Steve Probasco,

Amato Publishing;

Washington Blue-Ribbon Fly Fishing Guide,

John Shewey,

Amato Publishing;

Fly Fishers Guide to Washington,

Greg Thomas,

Wilderness Press;

Washington State Fishing Guide 9th edition,

Terry W. Sheely,

TNScommunications;

Washington’s Best Fishing Waters Map book,

Wilderness Press;

Washington Atlas and Gazetteer,

DeLorme.

Sidebar:

A Calendar of Expectations

(Compiled by Red’s Fly Shop)

JANUARY: Big fish month. Favorable flows under 1000 cfs, excellent water clarity. Sunny days may produce world class midge action. Trout start taking Skwala nymphs

FEBRUARY: Arguably the top month for nymphs. Skwala stonefly nymphs begin migrating and attract large pre-spawn rainbows. Last week marks the beginning of prolific olive Skwala hatches. Small blue winged olives begin to emerge.

MARCH: Mild weather, consistent water conditions, and a combination of BWO and Skwala fishing can give anglers up to six legitimate hours of action on dry flies. Look for BWO’s from 11:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. After Baetis switch to Skwalas and prospect seam lines and bank structure.

APRIL: Small BWO’s, Skwalas and March Browns strong through first two weeks. Caddis begin with the Grannoms size 12, start near the end of April. Caddis nymphs, in green and tan, are active and first two weeks of the hatch can be the most productive fishing of the year.

MAY: Mother’s Day Caddis, PMD’s, big yellow mayflies, and occasional salmon fly. Cloudy days are hot early on PMD’s and big yellows, switching to caddis in the

afternoon.

JUNE: River level transitions from spring clear to high colored summer flows. More large terrestrials: ants, bees, beetles, and grasshoppers tight to the banks. Some stonefly activity. Caddis offer sight casting afternoons into evening.

JULY: Flows near 4000 cfs. Slap cast summer stones, also called short wing, tight against the bank from a drift boat. Caddis after the sun goes off the water.

AUGUST: Water temperatures in the 60s, river still flowing around 4000 cfs. Grasshoppers and Summer Stones best.

SEPTEMBER:Transition from summer high water to fall low water. In 10 days, the river flow drops from 4000 cfs to around 1000 cfs and a major emergence of summer stoneflies takes place. Good dry fishing. BWO nymphs and terrestrials, some October Caddis. The bite can be great.

OCTOBER: Fall colors awesome, river flows less than 1000 cfs, middle of the month is prime for BWOs, Mahogany Duns, and October Caddis. BWO nymphs and dries are both productive. BWO’s and October Caddis are hot combo.

NOVEMBER: In warm weather years the fall Baetis may last all month. Best bite 10:30 am until 4 pm. Flow less than 1000 cfs and will remain there the rest of the winter. Stonefly nymphs are always present, and BWO nymphs are a prime food source. Carry midge and BWO patterns.

DECEMBER: Water temperatures in the low to high 30’s, nymphs and streamers most productive. Stones and Baetis nymphs and streamers on the swing in slower water. Some midge activity.

The Yakima River flows through countless fly fishing journals as a rainbow-rich anomaly in a state desperate for dream streams. Quick and cantankerous in the splintered log jams, widow-makers and shifting rocks of the mountainous upper reaches, and powerful, sullen and grumbling through the sun baked grasshopper grass and broken basalt in the desert canyon down below,the Yakima drifts downhill

for 215 miles like a wet chameleon with a sense of humor that changes disguises every few miles, and chuckles at the consternations of baffled fishermen scattered along the rocks and willows from Snoqualmie Pass to a confluence with the Columbia River near Tri-Cities.

The lowest 130 miles are on a sullen drift through irrigated melons and peppers, wine grapes and attendant pollutants of the lower Yakima Valley; smallmouth and channel catfish water and health department warnings abut toxic fillets.

I struggle to accept that upstream this abused gray river coursing through fertilized farms and belching from irrigation pipes in Wapato, Zillah, and Prosser morphs into the finest trout stream in Washington.

But it does, to the delight of fly fishermen throughout the state and beyond.

The transformation takes place a little north of Selah where the imposing concrete wall of Roza Dam divides the river like a cleaver, segregating the upstream mountain water for trout and caddis flies, leaving the downstream to catfish and pepper fields.

Those upper 85 miles represent the finest flowing dry and wet fly trout water in the

state.

Blue-ribbon is how some describe the rainbow river that glides downhill in the dam-to-dam serpentines between Keechelus Lake and Roza Dam. These 85 miles are storied with wild rainbows, catch-and-release brags, and hatch matching adventures.

In order to present the Yakima River in comprehensive detail it is being presented in two parts. This installment centers on the far upper river, Easton to Ellensburg. Part 2 will cover “The Canyon,” the magical 18 miles of sun-baked bank banging and hopper water between Ellensburg and Roza Dam.

Some hardliners packing three-piece travel rods and attitude sometimes argue the worthiness of this southeast flowing Cascade stream to be measured against Rocky Mountain destination rivers.

Others may lobby for the Methow or upper Columbia. But who listens. In this region the Yak perseveres as Washington’s paradigm of blue ribbon trout hope. And most of us who dip an oar in its cold water, drop Skwalas on the breaklines, or tighten into the electric jolt of a bank feeder find the Yak worthy; very, very worthy.

Steve Worley, routinely puts five guide boats on the river from his Worley-Bugger Fly Co. in Ellensburg. He defines the Yak as “Central Washington's premier wild trout fishery,” and in his eyes the fishing has been improving steadily since the early 1980's when the first set of progressive fishing restrictions was put in place.

Today’s blue ribbon trout fishery was jump started--somewhat reluctantly--in the 1990s when Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, (WDFW) with incessant prodding by fly fishing organizations, agreed to restrict the 75 mile section between the dams at Roza and Lake Easton to a no kill, no barbs, no bait, catch and release trout fishery. Support for trout protection from the salmon-steelhead focused WDFW was at best half hearted. They agreed to the restrictions with a “what-can-it-hurt” shrug and the justification that banning bait, debarbing hooks and putting a stop to catch-and-eat fishing might spare some of its prized but environmentally threatened salmon and steelhead smolts. The original bait ban and trout release restriction has since been extended the remaining miles to the Yakima’s less than pristine source--an outfall culvert from Keecheleus Lake.

Seriously managing rivers for trout fishing is still so far down on the WDFW priority list that it is invisible. Consider that the only somewhat current Yakima trout data now on file at WDFW was developed as addend to spring chinook restoration studies. Repeated requests for trout study money by concerned WDFW field staff have been rejected inOlympia denying state trout biologists basic and critical management data: fish per mile populations, trout growth, fishing pressure, creel census. Insiders confirm that when fish management isn’t steelhead and salmon focused, top WDFW managers still aren’t interested.

The slight is overlooked by most trout fishermen who prefer to embrace the default that resulted in rigid protections that now enhance naturally spawning wild rainbow trout-a first for Washington.

In his breakthrough book, Yakima River Journal (Amato Publishing, 1994), Northwest

Fly Fishing Editor-In-Chief Steve Probasco describes how in 1983 Tim Irish an Ellensburg native, became the first registered trout guide on the Yakima which also made him the first trout guide in Washington, and a bulls-eye for snide snickerings. From the clerks in the state guide licensing office to fellow fly-fishers there was open scoffing at Irish’s idea of trying to guide trout fishermen in a land of steelhead, salmon, sturgeon and even bass.

Today five guide shops specifically work the Yakima, dozens of guided float trips on any given day year-round, and still no WDFW plan for trout management. Not surprisingly, the river appears to be thriving on state neglect.

Steve Joyce cut his guiding teeth in Montana and now works at Red’s Fly Shop, the largest fly and guide operator on the river, running up to a dozen guide boats during seasonal peaks. “I can honestly say the Yakima is a challenging fishery,” Joyce grins. “It certainly has its days where it gives you a glimpse of how good it can be - with fish, and I mean nice fish, feeding on caddis or blue winged olives (BWOs) as far up and down the river as you can see. But it also has its tougher days, where you're forced to think outside the box and work hard to find a player.”

Neither Worley nor Joyce blink when describing the Yak above Roza Dam as premier trout water, and Jim Cummins, WDFW Yakima regional fish biologist agrees, adding that it can also be one of the most intensely fished trout rivers in the state. The effect of that “intense” fishing pressure is unknown, though. Not since 2003 has WDFW put together creel census surveys, angler pressure estimates or trout population censuses to guide future trout management.

Despite rumors of monster browns, 95 percent of the Yakima River trout are rainbow, with a few cutthroat, even fewer brookies and if a brown is around it’s a lonely stray. Most of the brookies are in the extreme upper reaches well above Cle Elum.

Which is where the Yakima is born half-grown, gushing from an outlet culvert in the dam at Lake Keechelus a sour, fish-poor agricultural irrigation reservoir at roughly 3000 feet elevation below the crest of the Cascades adjacent to I-90 east of Snoqualmie Pass. From the culvert it blows downstream past the USFS Crystal Springs campground in a torrent, and while small rainbows, cutthroats, and brookies are sometimes picked out of the eddies, pools and beaver ponds the premier trout water doesn’t begin for another 10 miles until the Yak escapes from Lake Easton the second and last impoundment above Ellensburg.

The catch-and-release rule applies to rainbows, cutts and browns, but not for brookies. In their campaign to ravage brook trout populations in streams with native char, WDFW has made an exception to the no-trout rule, and allows anglers free reign on the non-native brookies between Easton and Keechelus lakes: no daily or size limit on brook trout.

Downstream from Lake Easton the first decent public launch and wading access is at a WDFW site on East Nelson Siding off I-90. Several hazardous miles below is the Bullfrog/Three Bridges access. Both put-ins lead to log jams, widow makers and bottom banging treachery and are not recommended for drift boats or novice boatmen. Adding to the discouragement is that trout in this upper water, above South Cle Elum, are uncommonly small averaging less than 9 inches, compared to 10 inches and up a few miles further downstream. Fishing pressure in this unfriendly water, though, is also down.

The Yak grows its first serious trout legs at and below the confluence of the Cle Elum River (which quick steps under I-90 not far from the confluence) and steadily improves as it swirls and rolls into South Cle Elum (a WDFW launch south of I-90). Called The Flats or Flatlands by local trouters, the Cle Elum stretch is a reasonably manageable chunk of boating water with skitches of public bank access. Here, boat and bank anglers work through a series of braids and runs and green-bottomed pools with two miles of wade and cast access from the Hansen Pond Road.

This winding rock and riffle torrent upriver from Thorp is the sweet love of Ellensburg outfitter Steve Worley. “Above Ellensburg the Yakima offers more diversity, cleanlier water conditions and no crowds.” he says. The little main-street town of Cle Elum is squarely in the center of this water. A couple of miles southeast is a WDFW access/launch at the Teanaway River junction. (From I-90, Exit 85 and follow Old Hwy. 10 toward Blewett Pass Highway 970). This small dot on the state highway map is a major demarcation line for fly fishermen.

Above Teanaway launch are the Cle Elum Flatlands, and below the beginning of Canyon Water. With a few obvious exceptions most of the water downstream from the Teanaway River appears as a blue line in the bottom of a steep-walled canyon well down from Old Hwy. 10, a climb that discourages most bank fishermen. On several occasions though I found it more than worthwhile to slog and skitter the steep grade to fish water well off the beaten path. One excursion did cost me the tip section of a favorite 4 wt. Sage, but it was my fault and I’ve since recovered.

The John Wayne Trail is public path important to bank fishermen. It follows an old railroad grade along the river south and east from Cle Elum. The trail is a popular walk and wade route for fly guys. Mountain bikers sometimes pack in for overnight bike-and-fish. If you go, I recommend packing fly-weights and boots and hiking to fish water in shorts. Any hike in this piece of the world is hot and steep.

Below the Teanaway is where, in my estimation, the Yakima enters Premierdom, spilling into a trouting wonderland for boaters that can be savored for roughly 10 miles; two-thirds of the 16-mile float to a diversion dam take-out at Thorp. (If unchained, a DOT storage site on Hayward Roadbelow Thorp Bridge offers a rough take-out alternative to continuing downstream to the WDFW take-out above the Diversion Dam, and eliminates the Thorp section of river which according to WDFW has the thinnest trout count per mile in the river. There are, however, some large trout--20 inch plus--taken here. Just not a lot of them.

High above the river pinned onto the stark canyon wall is Old Hwy 10 which follows the Yakima at a comfortably lofty distance southeast from the Teanaway access to Hwy. 97 just outside of Ellensburg. At the bottom of the canyon, well below the highway and away from major roads and barking dogs, the river twists and turns, grinds and grumbles through riffles in a slow, steady drop between banks of cottonwood and quakies. Elk, mule deer and coyotes slip into the shadows, and the river offers up every type of river and fishing condition imaginable, pockets for the picking, overhangs, bottomless pools, deep sullen runs, and sweeping tailouts.

A novice at the oars will bang, hang, spin and ricochet but overall there is little truly dangerous water, especially in the fall when October caddis and BWOs are coming off, trees drip with gold, the irrigators have sluiced off all they want and the river runs low and clear.

Bigger trout may hang under cutbanks in the canyon down river from Ellensburg, but the combination of scenery, color and cold, fat 10 to 20 inch rainbows (I’ve heard of 22 inchers here, but have yet to see one) that meshes in the upper Canyon is without parallel. There was a five year stretch when on the last weekend in September I never missed dropping the old Eastside drift boat into Teanaway launch and spinning down river. I need to do that again.

According to those 2003 WDFW studies the Thorp section has the fewest number of rainbows in the river, averaging 244 per mile compared to the river-wide average of 677. The highest concentration per mile is in the lower Canyon section above Roza with1129 rainbows per mile-one trout in every 4 ½feet of river.

It’s easy to see why Worley’s bias favors the upper canyon around Cle Elum.

“The river just gets better from year to year,” he says, adding, “There’s not a significant increase in trout numbers, but yet (we’re catching more) bigger resident trout.

“Hatches are seasonal and change from year to year depending on water flows and conditions. But yes we are seeing thicker denser hatches on average each season. There as an incredible Light Cahill hatch this past September.It was extraordinary.”

Both Worley and Joyce agree that if they had to pick one Yakima River rod it would be a 9’ 5-weight.

Joyce, who fishes mostly below Ellensburg said his rods “would be stiffer than softer, to throw big dries and small dries, and double nymph rigs and still handle heavy stoneflies and streamers. We use a 9' 5X tippet to fish a small dry fly hatch, but typically run 3X to our big dries which helps turn those bugs over to tuck them underneath the brush canopy and rip your fly off of grass stems. For nymphs we run 3X fluorocarbon to the top fly and 5X between flies, and for streamers we run as big as 1X and 2X - again it helps turn the fly over.”

In his 13-years on the river, Worley has settled on, “a floating line for dry fly fishing and nymphing. Streamers are also effective,” he said, recommending, “Tippets of 4x-5x for dry line fishing with surface and subsurface bugs. A short fast sinking tip is also recommended especially during the summer months when irrigation release flows are high and for streamer fishing. Type V or VI in seven foot lengths. Nothing over 10 feet. Too much belly,” he explains.

I asked Worley if forced to settle on one fly and one rod-line combination for the upper river what that outfit would be. His response was unhesitating, “No. 8 Yak Stonefly, using a Scott GII with a Scientific Angler Expert Distance line.”

Packing fly boxes for a trip to the Yak is a bit like picking girl friends and fishing buddies—take your best guess and sort out the fine points as you go.

Depending on where you are on the river, what the weather is doing, water and air temperatures, month on the calendar, water level and clarity and what rock you’re standing on—your pattern selection could run from dainty size 24 midges to lumbering Size 6 Stimulators or fish-size sculpin-imitating dredgers.

Since salmon populations have been enhanced in the trout water the rainbows have been showing a distinctive preference, at times, for flesh flies, eggs, salmon fry and smolt patterns, according to Steve Worley.

When I picked the brain of Steve Joyce it was his opinion that, “Talking about hatches is relative to whether the fish are actually keying in on them - and not necessarily the number of bugs you see.

“For example - we've had some great Skwala years, and some where it seems like the hatch just never really gets going. We've noticed a couple of reasons for this. One is that if we get a big punch of runoff at the beginning or middle of this hatch, it tends to slow it down - if this happens repeatedly, it hasn't fully recovered by the time the Skwala window is past.

"Another reason for slow Skwala fishing can be low water conditions. Even though the bugs are hatching and the river is in great shape, there may not be enough water for those weak side banks to fill up and fish to move into the shallow insides to eat the Skwalas. As a result, fish are fighting for prime lanes on the strong side and all fisherman are targeting the same zones. It doesn’t take them long to learn not to eat there.

“Factors that may tale the edge off Skwala fishing are sometimes conducive to alternative hatches such as March Browns, PMD's, and even BWO's - which are gravel bottom riffle bugs.

“These hatches are productive when water conditions are low enough to define the ledges and seams in the center of the river yet high enough for fish to spread through out the flat water zones.”

The list of fishable hatches on the Yak is almost baffling.

According to charts that Steven Worley posts on the Worley Bugger web site, a well-rounded box needs: BWO, mahogany duns, March browns, caddis (most prolific fly on the upper and lower river), Grannom (Mother’s Day caddis), sedge, assorted salmon flies, PMD, yellow Sally, a wide selection of terrestrials, craneflies, golden stone, spotted sedges, big yellow mayflies, little tan sedge, green drake, summer stone, hoppers, Cahills and October caddis.

And that doesn’t include the basic sculpin imitations. Sculpins are a major food source in the Yak, according to Worley, especially for the largest trout.

While wet and dry variations of midges (Chironomidae), Blue Winged Olive mayflies (Baetidae) and to a lesser degree caddis are the January-December bread and butter patterns nothing blows lightening through the fly shops like stonefly news.

Winter stones (Capnidae) pop out in January, February and taper into March. March is Spring Stone and Skwala time. Summer stones (Claassenia sabulosa )start coming off in June and peak in July, August and September. A hatch of Golden stones (Hesperoperla pacifica / Calineuria californica) comes off in May and June, but it’s usually minor compared to the salmon, caddis and mayfly (Mahogany duns, and green drakes, according to Worley) that also hatch then.

For some Yakima purists heaven is defined in the too-brief flutter of Salmonflies (Pteronarcys Californica) in April, May and maybe June.

Downstream there are grasshoppers, up here caddis and stones. A Yellow Sally Stimulator or heavily dressed caddis will be sucked down by trout feeding on all three. If, for the Thorp to Cle Elum swing, I had to rig with one dry and one wet and nothing else, the dry would be a No. 8 Stimulator and the wet a No. 10 black Woolly Bugger, but if the fish master cuts me a little latitude I’ll cheat in a handful of elk hair caddis and maybe a beadhead Brassie and for sure a Prince.

Best time to fish the Yak?

Spring, according to the guys are on the river every month of the year.

For Worley, “April has to be one of my favorites. The March Brown hatch is fantastic. But September is a pretty fine month as well.

Joyce’s favorite slice of river time flows from March 1 to May 15. “We get so many good hatches during that window that there will be periods during the day where you'll throw both dries and nymphs with success, and the nymphing is usually good outside of that (dry) window. We start with Skwalas and BWO's, then get into the March browns, followed by caddis and PMD's. The pre spawn rainbows are aggressive, feisty, and beautiful.”

There’s always a down side to even blue-ribbon rivers and for the Yakima that downside is valley floor irrigation.

The big reservoirs on the east side of Snoqualmie Pass are Bureau Of Reclamation (BOR) water stores for downstream irrigators in the Kittitas and Yakima valleys, and for several mid-summer months at the peak of the growing season this picturesque river descends into sluiceway hell and the blue-ribbon runs brown. Joyce said he’s seen the river romp from 700 cfs with exposed gravel bars to 9000 cfs with an unbroken surface bank to bank.

Releases into the river are based on irrigation demands and water rights, with no thought to fish or fishers, except for chinook salmon. Typically, the irrigation sluice kicks in late June, peaks in August and drops through September; a timing schedule that benefits orchards, field crops and wild chinook salmon spawn.

According to long-time river fishers cfs flows from 500 to 1500 are ideal for boaters and waders. Wading is a risky option to about 2000 cfs and stronger than that the river is strictly a boat show. Brown water or blue, trout feed and the river is usually clearer upstream from the Teanaway during peak sluice season.

Don’t let the color stop you—it’s always blue ribbon time on the Yakima.

Yakima River Notebook:

When: Open year-round, best March-May before irrigation releases and in late September-October after irrigation ends.

Regulations: Catch and release all rainbow, cutthroat and brown trout, no bait or scents, single barbless hook. Brook trout may be killed in the extreme upper river between Lakes Keechelus and Easton.

Where: Cle Elum River confluence to Thorp, with special attention to the Cle Elum Flats and canyon water below the Teanaway junction.

Headquarters: Either Cle Elum or Ellensburg. Lots of motels and private camping in both towns.

Appropriate gear: 9’, 5-wt. rod, floating and sink tip lines, 5X tippet for small flies, 3X to flip big dries and 1X to 2X for streamers. Waders and good shoes a must, pontoon boats are perfect for this section. Flatlands to Thorp okay for rafts and drift boats. Bring good Polorized glasses, extra tippets and lots of flies.

Useful fly patterns: Caddis and blue winged olives are the most prolific. Also carry plenty of stonefly variations, Skwalas, Stimulators, midges, PMDs, salmon fry, egg and egg patterns. Prince and Woolly Buggers are always welcome. (See chart).

Advisable necessities: Breathable waders (Neoprene’s in the winter), polarized sunglasses, plenty of drinking water, day pack, fluorocarbon spools for tippets, sun protection, big hat.

Non-resident license: Annual freshwater, $43.80, 1-day $14.

Fly Shops and Guides: These local shops offer flies, tackle, current information, fly guides, float trips, and shuttle service for the upper Yakima.

Worley Bugger, Ellensburg,

888-950-FISH,

www.worleybuggerflyco.com;

Red's Flyshop,

Ellensburg Canyon,

(509) 929-1802

www.redsflyshop.com;

Yakima River Fly Shop,

Cle Elum,

509-674-2144

www.tightlinesangling.com.

The Evening Hatch,

Ellensburg,

1-866-482-4480,

www.theeveninghatch.com

Yakima River Angler Guide Service,

Selah

509-697-6327,

www.yakimariverangler.com

Books & Maps:

Yakima River Journal,

Steve Probasco,

Amato Publishing;

Washington Blue-Ribbon Fly Fishing Guide,

John Shewey,

Amato Publishing;

Fly Fishers Guide to Washington,

Greg Thomas,

Wilderness Press;

Washington State Fishing Guide 9th edition,

Terry W. Sheely,

TNScommunications;

Washington’s Best Fishing Waters Map book,

Wilderness Press;

Washington Atlas and Gazetteer,

DeLorme.

Sidebar:

A Calendar of Expectations

(Compiled by Red’s Fly Shop)

JANUARY: Big fish month. Favorable flows under 1000 cfs, excellent water clarity. Sunny days may produce world class midge action. Trout start taking Skwala nymphs

FEBRUARY: Arguably the top month for nymphs. Skwala stonefly nymphs begin migrating and attract large pre-spawn rainbows. Last week marks the beginning of prolific olive Skwala hatches. Small blue winged olives begin to emerge.

MARCH: Mild weather, consistent water conditions, and a combination of BWO and Skwala fishing can give anglers up to six legitimate hours of action on dry flies. Look for BWO’s from 11:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. After Baetis switch to Skwalas and prospect seam lines and bank structure.

APRIL: Small BWO’s, Skwalas and March Browns strong through first two weeks. Caddis begin with the Grannoms size 12, start near the end of April. Caddis nymphs, in green and tan, are active and first two weeks of the hatch can be the most productive fishing of the year.

MAY: Mother’s Day Caddis, PMD’s, big yellow mayflies, and occasional salmon fly. Cloudy days are hot early on PMD’s and big yellows, switching to caddis in the

afternoon.

JUNE: River level transitions from spring clear to high colored summer flows. More large terrestrials: ants, bees, beetles, and grasshoppers tight to the banks. Some stonefly activity. Caddis offer sight casting afternoons into evening.

JULY: Flows near 4000 cfs. Slap cast summer stones, also called short wing, tight against the bank from a drift boat. Caddis after the sun goes off the water.

AUGUST: Water temperatures in the 60s, river still flowing around 4000 cfs. Grasshoppers and Summer Stones best.

SEPTEMBER:Transition from summer high water to fall low water. In 10 days, the river flow drops from 4000 cfs to around 1000 cfs and a major emergence of summer stoneflies takes place. Good dry fishing. BWO nymphs and terrestrials, some October Caddis. The bite can be great.

OCTOBER: Fall colors awesome, river flows less than 1000 cfs, middle of the month is prime for BWOs, Mahogany Duns, and October Caddis. BWO nymphs and dries are both productive. BWO’s and October Caddis are hot combo.

NOVEMBER: In warm weather years the fall Baetis may last all month. Best bite 10:30 am until 4 pm. Flow less than 1000 cfs and will remain there the rest of the winter. Stonefly nymphs are always present, and BWO nymphs are a prime food source. Carry midge and BWO patterns.

DECEMBER: Water temperatures in the low to high 30’s, nymphs and streamers most productive. Stones and Baetis nymphs and streamers on the swing in slower water. Some midge activity.

Yakima River Hatch Chart

Courtesy of

Yakima River Angler Guide Service,

509-697-6327,

www.yakimariverangler.com